1.1 SW Definition

The alien

Far away in the galaxy, there's a species of aliens who believe in a vast multiverse, filled with an infinite number of

worlds; they live in just one. These aliens have a special ability to teleport to other worlds. The process seems

simple: an alien must learn about a life-form from another world, think and act like it, and then, one day after falling

asleep, they wake up in that new world, transformed to fit right in.

However, this unique way of traveling has a big downside — amnesia.

The farther away they travel, the more they forget who they

are and where they came from. This loss of memory is a major problem because to get back home, they need to know

both where they are and where they originated from.

Without this crucial knowledge, they find themselves stranded in the new world.

One such alien has teleported himself (perhaps, by an accident) to Earth — a planet made of rocks and magma,

covered by a thin layer of soil,

water, and gases, orbiting a young star in the cold expanse of space. This planet teems with diverse life forms, which

the alien refers to as shape-shifters because of their constant physical transformations.

Their bodies grow by absorbing

elements from their surroundings until they reach a certain size and then disintegrate into atoms and molecules scattered

across the planet, to be mixed with other materials, and eventually aggregated into new beings. This perpetual cycle of growth and

disintegration repeats continuously and never stops on this planet.

Unlike the alien, the natives cannot survive in the vacuum of space or travel across galaxies; they are bound to this planet.

One type of these shape-shifters, known as humans, has developed the ability to transform simple abstract concepts into

tangible forms. They design and construct buildings, machines, and social structures, and consider themselves to

be a highly advanced species, superior to all other life forms on the planet. For some reasons they thinks

they are much better than monkeys, another group of shape-shifters that has only recently begun to exhibit similar

capabilities.

Despite their achievements, humans are largely unaware of the vast expanse of knowledge that remains undiscovered. They

have no idea how little they actually know, nor can they anticipate how much there is yet to learn. It remains an open

question who will access this hidden knowledge first — humans, monkeys, or perhaps another species altogether.

Anyway, now he is one of them. Due to the amnesia, he doesn't clearly remember his

past, but he feels a deep sense that he doesn't belong on Earth and that he must eventually return home. To make this

possible, he needs to determine his current location and remember where he came from.

To start, the alien gathers information about Earth and its residents. He learns about particles, the void, and the

physical laws of the universe from physics textbooks. A priest shares insights about miracles and the divine aspects of

human nature. A general talks about honor and duty. Meanwhile, children from a nearby school suggest

him to write a letter to Santa Claus, believing that Santa might perform a miracle and help him get back home.

The alien must discern which stories are likely

to be true and which are not. He recognizes some universally acknowledged truths across all communities, such as not

crossing the street on a red light, washing hands before eating, and objects falling when dropped.

However, beyond these straightforward truths, he encounters stories that contradict each other. Some of these

contradictions can be resolved by viewing the stories as complementary, addressing different aspects of the same world.

For example, the general's emphasis on honor and duty might align with both the scientific and religious narratives.

Yet, the narratives from the scientist and the priest are more challenging to reconcile, particularly when it comes to

human nature. Both science and religion claim the authority to define, explain, and manage human nature, providing

vastly different perspectives on what it means to be human, human's origins, and human's purpose. These differing accounts

represent a significant point of contention he must navigate.

The questionary

The alien realizes that the narratives of science and religion cannot both be entirely true. This means he either

lives in a world governed by scientific principles or one defined by religious doctrines (and there are so many of them).

It is so easy to drawn in this ocean of various teachings. To make progress the alien decides on a structured approach and sets up a series

of checkpoints to test these teachings rigorously:

1. **Self-consistency**: The alien looks for narratives that provide a coherent description of the world. While no story

he's encountered is without flaws, and all exhibit some inconsistencies, he finds that some are significantly more

coherent than others. This coherence is a crucial marker of a narrative's potential validity.

2. **Empirical validation**: He tests the stories against observable and measurable evidence. For example, if a

narrative claims an apple is on a tree, but he sees no apple, he considers the story likely false. This reliance on

empirical evidence helps him ground the narratives in observable reality.

3. **Experimental testing with time manipulation**: Possessing a time machine that can accelerate time, the alien uses

this tool to test spiritual and transformative processes, like achieving enlightenment through Buddhism, in just a few

hours instead of years. This unique method allows him to rapidly assess the efficacy of practices that would otherwise

take a lifetime to evaluate.

If these initial methods fail to conclusively verify a story, the alien employs additional, somewhat subjective but

still valuable, criteria:

4. **Credibility of the source**: He considers the reliability of the person or entity providing the information.

Stories from known unreliable sources are deemed less trustworthy.

5. **Historical persistence**: The alien values stories supported by historical documentation more than recent

creations. The longevity of a narrative or practice often lends it greater credibility, suggesting its resilience and

relevance through time.

6. **Community endorsement**: Finally, he assesses the breadth of a story's acceptance. A narrative believed by a large,

diverse community is considered more credible than one upheld by only a few individuals.

7. **Predictive Power**: The predictive capabilities of scientific theories are scrutinized, assessing their ability to

accurately forecast future observations or phenomena. Similarly, the predictive prophecies or promises made within

religious texts may be assessed for their fulfillment or accuracy.

8. **Ethical Framework**: The moral and ethical frameworks presented by both science and religion are examined for their

alignment with universal principles of justice, compassion, and fairness. The alien evaluates whether each worldview

promotes values conducive to harmonious coexistence.

Through this multifaceted approach, the alien aims to sift through conflicting narratives to uncover which—if

any—accurately describe the world he currently inhabits.

Indeed, these check points help him to identify certain narratives as belonging to the realm of

fantasy, never to be mistaken for genuine truth. For example, the tale of Santa Claus (SC), exhibits several

characteristics indicative of its fictional nature.

1. Firstly, the story of SC starkly contradicts common knowledge derived from everyday experiences. The absence of any

documented sightings of flying reindeer casts doubt upon the plausibility of the narrative. Moreover, the storyline

violates fundamental principles of physics, such as mass conservation and the finite speed of movement.

2. Furthermore, empirical evidence such as satellite imagery and video recordings, fails to corroborate the existence of

SC or his alleged activities at the North Pole. Instances of fraud committed by adults fooling their kids and captured by

surveillance cameras during Christmas

festivities only serve to compound the skepticism surrounding the narrative.

Drawing upon this wealth of evidence, the alien arrives at a tentative conclusion, acknowledging the high probability,

though not absolute certainty, that the story of SC is indeed a fabrication. Initially perplexed by the festive fervor

surrounding Christmas celebrations in certain societies, the alien eventually recognizes these customs as mere social

conventions, devoid of any objective basis in reality.

So far, so good. However, distinguishing between the complex worldviews of adults is a more challenging task. To

accelerate his investigation, the alien creates a short questionnaire designed to capture the key elements of

teachings aiming at the description of the whole world:

1. **Ontology**: What does this world consist of?

2. **Cosmology**: How does this world function?

3. **Metaphysics**: Why does the world function in this way?

4. **Identity**: Who are you?

5. **Practices**: What do you do?

6. **Values**: Why do you do it?

7. **Metanarrative**: What is the overarching story?

These questions aim to provide a concise overview of the key components that make up each worldview.

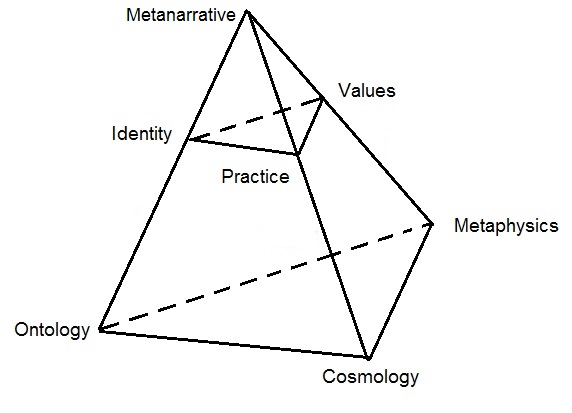

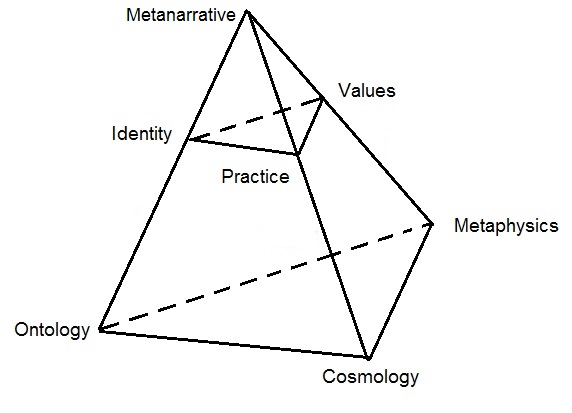

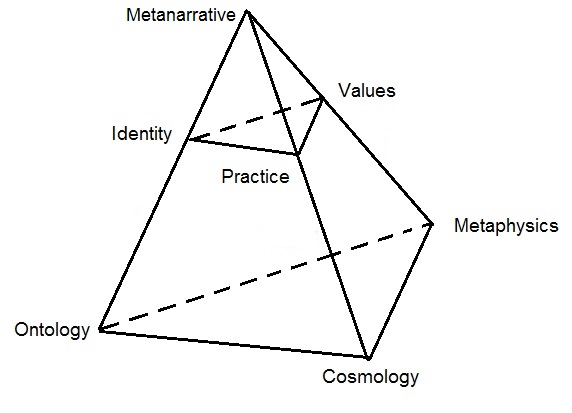

Figure 1.1 provides a schematic representation of this questionary.

Figure 1.1 Schematic representation of the questionary

The first question in this questionnaire, dealing with ontology, aims to list and explain the fundamental components of

this universe. While an exhaustive description is not feasible, and some elements might remain obscure until further

elaborated in subsequent sections, this section is meant to lay down the key elements:

a scientist might describe the world as

composed of atoms and voids, a religious person might see it filled with divine entities and miracles,

and a general could view it in terms of alliances and potential threats.

The next part, concerning cosmology, is

about the interaction and evolution of the elements introduced in the ontology section, explaining how people and their

environment influence each other over time.

The third question focuses on metaphysics, querying why this particular universe description was chosen over any other.

These initial questions primarily explore the external world. The subsequent three questions touching on

identity, practices, and values, narrow the focus to specifically human concerns.

The "Identity" question probes the notion of human nature, or whether such a entity exists at all.

The practices question seeks to clarify what actions people in this universe typically engage in and what behaviors are

considered appropriate or inappropriate.

The values question attempts to establish what is regarded as morally good or bad, adding a layer of ethical judgment to

the otherwise neutral descriptions of the self and the universe.

The concluding section, the metanarrative, weaves all the previous responses into a single, cohesive story about the

individual and the world. Without this overarching narrative, the questionnaire risks being a collection of disjointed

stories with little coherence and infested with contradictions. The metanarrative serves to unify these narratives,

smooth over any apparent contradictions, and offers one interpretation among many possible others.

Disguised as a social scientist, the alien approaches random people on streets, asking them to provide concise

responses (no more than one page) to his questionnaire. Surprisingly, most respondents, except professional

philosophers, are able to provide answers and craft short narratives describing their universe and themselves.

Despite being vague and imprecise with details and using poorly defined terms, these narratives are more or less

coherent and tell some sort of story. As for the philosophers, they often stumble at the first question, hindering

their progress on subsequent inquiries.

The alien then organizes these stories into distinct categories that represent different communities such as scientists,

priests, and warriors. He begins to suspect that these narratives may reflect parallel worlds that people have either

inhabited or can somehow perceive. He labels the collection of stories from a particular community as a "Storied World"

(SW).

Comments on Storied Worlds

It might seem natural to view the metanarrative, which weaves the responses from the questionnaire into a single

comprehensive story, as the ultimate goal and the most significant outcome of this project. This could lead to the

assumption that once the metanarrative is established, the individual responses to earlier questions can be disregarded.

However, this perception is somewhat misleading. The diverse collection of stories generated by people's answers to

specific questions is just as crucial as the overarching metanarrative that emerges from these stories. Indeed, it might

be more accurate to consider the metanarrative as just another narrative within this collection, rather than the final

or definitive product of the questionnaire.

The collection of stories generated by the questionnaire cannot be simplified into a single narrative for several

reasons. Firstly, there isn't a direct one-to-one match between the questionnaire and any metanarrative that might be

derived from it. With a rich background of diverse stories, multiple metanarratives can be crafted, each offering

different interpretations or emphases. A single metanarrative cannot encapsulate the full range of stories produced by

the questionnaire. Thus, discarding the individual responses after creating a metanarrative would result in a

significant loss of information. This would be akin to replacing all scientific literature, encompassing various

theories and perspectives from different scientific schools, with a single mainstream teaching ignoring competing

theories and

hypotheses. Such an approach would overlook the richness and complexity inherent in the multiple viewpoints and reduce

the depth of understanding.

Secondly, the collection of stories derived from the questionnaire represents a dynamic body of knowledge that can

expand and evolve in numerous ways over time. In contrast, a single story or metanarrative is by nature a complete and

static entity. It typically has a clear beginning, middle, and end, resembling a biography that starts with birth,

progresses through life, and concludes at the grave. Any sequel would inherently be about a different subject; the

original protagonist's story is completed.

On the other hand, the anthology of stories from the questionnaire is perpetually open-ended. It's never truly complete

and has the potential to grow indefinitely. While the foundational materials provided by previous contributors may guide

new developments to some extent, the overall structure is so rich and multifaceted that it can readily incorporate

fundamentally new stories. This ongoing, ever-evolving nature ensures that the body of stories remains vibrant and

adaptable, reflecting new insights and perspectives.

Each question in the questionnaire doesn't demarcate a strictly isolated area of inquiry. Rather, the answers to

different questions often overlap. For example, in some narratives, such as those found in Buddhism, cosmology and

psychology are so intricately intertwined that it becomes nearly impossible to separate the two. As a result, a

description of cosmology remains incomplete without incorporating elements of psychology, and understanding psychology

necessitates some explanation of cosmology.

Unlike a single narrative that requires internal consistency, a collection of stories can encompass a variety of

narratives that may contradict one another. These contradictions within the collection do not undermine its value;

rather, they enhance its flexibility and capacity for adaptation. This diversity allows the body of knowledge to remain

open and responsive to new developments, as it can accommodate a wide range of perspectives and insights. Thus, the

ability to include conflicting narratives makes such a collection a more dynamic and versatile repository of knowledge.

Historical examples of such collections of stories include the Vedas, Buddhist texts, the Bible, and

scientific literature. These

narratives can be passed down orally from one generation to another, written on paper, or stored digitally on the

Internet. No matter how they are expressed, these collections are characterized by their irreducibility; no single

narrative, including a metanarrative, can fully encapsulate the entire subject matter.

These collections often contain redundancies that may lead to contradictions, reflecting the contributions of multiple

authors rather than a single voice. The process of creating these stories is not confined to a brief period but can span

centuries or even millennia, evolving over time as they are shaped by countless contributors. This extended and

collaborative nature of storytelling adds depth and diversity to the knowledge contained within these texts, making them

rich resources for both contemporary and future generations.

A key feature of such a collection of stories is its conceptual completeness, meaning it possesses the resources

necessary to evaluate the truth value of any statement. This completeness ensures that any inquiry concerning the self or the

universe can be appropriately addressed within its framework. While not every question may receive a definitive answer,

the crucial aspect of these collections is that they offer a conceptual background capable of addressing any question,

regardless of the specific vocabulary used to express it.

This ability to accommodate and process diverse inquiries makes these collections incredibly valuable. They provide a

comprehensive platform where various perspectives and interpretations can be considered and scrutinized, contributing to

a deeper and more nuanced understanding of the world.

The size and scope of such collections can fluctuate over time. For example, the volume of scientific knowledge today

far exceeds what was available just a few hundred years ago. Additionally, the extent to which this knowledge is

internalized varies significantly among individuals and even within the same person at different stages of their life.

This variability in knowledge acquisition reflects not only the dynamic nature of information growth and change but also

individual differences in learning, interest, and capacity. It highlights how personal and societal growth in knowledge

is not static but continually evolving, influenced by educational opportunities, cultural shifts, and technological

advancements.

On the method

Because of the all-inclusive nature of the Storied World, the method of dealing with such a complete body of

knowledge has some

peculiarities. According to scientific method, you formulate a hypothesis, test it against established knowledge and

then depending on the outcomes of that test either accept or reject that hypothesis. In our all–inclusive collection of

stories the body of the hypothesis comprises the whole world, and hence no knowledge is left beyond that body to test it

against. In other words, there is no such thing as established knowledge residing beyond that storied-world (which itself is our

hypothesis), and if one storied-world contradicts another, there is no reference point beyond the body of the hypothesis

to establish its truth value. Unless, of course, we are prepared to postulate some privileged knowledge and methods of

dealing with such knowledge. And if we do, these privileged methods and knowledge,

once established, must be taken for granted and never questioned afterwards.

Consider as an example the story of the “Big-Bang”. According to many religious teachings

this story does not make sense. On the other hand, it makes perfect sense within the scientific interpretation.

In either case the truth value of that story is assessed against a larger body of knowledge formed by a particular SW.

To assess the truth value of different stories from the vantage point of some “impartial” observer (not

attached to any particular SW), this observer would have to step outside of every possible SW.

However, no Storied World implies no language and, hence, no principles whatsoever to guide our decisions.

If we don’t want to succumb to the existential vacuum here, we have to postulate rules, perhaps, grounded

into some minimalistic collection of stories, upfront. These rules are needed to provide us criteria to rank other

stories (see Gadamer’s “Truth and Method” for in depth analysis of this subject).

So, what kind of rules we may implement in order to evaluate different storied-worlds?

1. To start with, we may require Storied Worlds to be represented by self-consistent collection of stories (otherwise

we can not comprehend them).

2. It would be nice also for these stories to be consistent with an empirical

evidence (so that we can verify them through practice).

3. We may want also to add rules pertaining to ethical principles, or referring to our quality of life,

or the notion of sacred, etc.

A complete collection of such rules shall provide criteria to rank existing

storied-worlds. The same rules would be used to channel the development of new storied-worlds (by imposing

constraints on the kind of the worlds we can to create).

Why did I choose this particular set of rules rather than some other set?

I can explain it with the reference to some aesthetic considerations or quote an “unreasonable efficiency” of the

logically-consistent bodies of knowledge or highlight the quality of life and importance of human beings.

But then other people may argue that we

shall consider only those stories and rules which promote the well-being of cats, because cats are important and

this fundamental truth is hardwired into the human nature and they can feel it etc.

It is very hard to argue with a human nature. To save time and energy, I just cut it here and postulate the

aforementioned principles guiding the development of new

stories. I believe, these principles are sufficiently general to let us analyse and develop a rich variety of new SWs, on

the one hand, and, at the same time they are sufficiently constraining to eliminate unwanted entries. I will elaborate

further on these principles through chapters 1 to 3 to make them more structured and convincing.

The critical point to remember,

however, is that the rationale behind them is never watertight. There is always place for an alternative set of rules

that would provide other means for ranking different storied-worlds. On the other hand, the choice is never completely

arbitrary. To be sustainable, a SW must respect at least some norms of ethics and be consistent with the laws of

physics. In other words, vocabularies do not exhaust the whole world. There are practices and experiences that transcend

stories and open the door towards other realities in our lives which surpass linguistics and may provide extra anchoring

points to justify our vocabularies.

Contradictions

Both humans and aliens value the communication of their experiences through self-consistent, coherent stories, which

narrow down interpretations to what we commonly accept as truth. In a self-consistent story, humans and aliens starting

from the same premises arrive to the same conclusions.

From the management perspective having one single description of the world helps to decide the best

course of actions. Coherent stories also help people to communicate with each other - if a story is

inconsistent we often say it does not make sense.

Yet, stories we tell about ourselves and the world around us are often infested with contradictions. The degree of

the logical cohesion present in these stories and the attitude towards contradictions varies from one storied-world to

another. In some teachings (e.g. science) contradictions are introduced pests to be eradicated - the smaller the

number of contradictions the better the theory. On the other hand, in many religious schools (e.g. Zen Buddhism,

Taoism), a contradiction is a critical and irreducible part of the teaching - get rid of all contradictions

and the teaching is gone.

The exact meaning of the word contradiction depends on the context. It could be referring to

contradictions between two statements (e.g. one statement saying “this is

white”, and another statement saying “this is black”), contradictions between theory and experimental evidence (theory

says “this is white”, but we can see it is black), contradictions between intentions and reality (he wants to maintain

healthy life-style but smokes), contradictory psychological states (love and hate the same person),

contradictions in social life (individual vs collective goods) etcetera.

The ubiquitous nature of contradictions in our lives has been vivdly expressed by Paulo Coelho -

“we are in such a hurry to grow up, and then we long for our lost childhood. We make ourselves ill earning

money, and then spend all our money on getting well again. We think so much about the future that we neglect the

present, and thus experience neither the present nor the future. We live as if we were never going to die and die as if

we had never lived.”

A succinct definition of the contradiction that would serve our purpose reads:

two statements are contradictory if we cannot believe in both.

Summary and concluding comments

Ideally, the alien would prefer clear, black and white answers to his questions, which would allow him to easily

distinguish between false and true descriptions of the world. However, he soon realizes that the reality is far more

complex. Instead of a clear demarcation between truth and fiction, he encounters varying degrees of plausibility.

The alien discovers that none of the criteria intended to sift through the narratives and isolate a single truth is inadequate.

For example, while each narrative presents

itself as a logically more-or-less coherent story, none are entirely without flaws — each has inconsistencies and imperfections. Moreover, for

some narratives, contradictions are not just present

but are an essential, integral part of the story.

The alignment of stories with empirical evidence is not straightforward either, as the selection of evidence itself is

influenced by what people believe and practice.

Experiments with time machine illustrate how individuals absorb and reflect the beliefs and convictions

of their own cultural contexts. This in turn suggests

that the source of knowledge, its endurance over time, and community endorsement are all factors that shape belief

networks, yet these alone do not yield definitive answers.

Despite these discouraging findings, the alien remains hopeful about discovering principles to distinguish between real

and imaginary worlds. To deepen his understanding, he retreats to a library, immersing himself in science and philosophy

texts.

Years of rigorous study yield mixed results. On the one hand, he is disheartened to find that, despite humanity’s

significant progress, major gaps persist in their understanding of reality, knowledge, and ethics (see Appendix D2 for

details). Fundamental questions remain unanswered, and intrinsic barriers hinder further exploration of these mysteries.

On the other hand, these limitations open an opportunity for the alien to forge his own solution. Rather than relying on

established definitions of "real worlds", he can construct a new one. His preliminary insights suggest that this

definition should be broad enough to encompass a diverse range of teachings within a unified framework — something akin to

a multiverse. He recognizes that many of the stories he has encountered so far merit being called "real," yet contradictions

within and between these narratives demand resolution.

This new definition must be both coherent and intuitively satisfying — one he can genuinely embrace.

Beyond these aspirations, he remains open to wherever this intellectual journey might lead.

With this vision in mind, the alien sets out on the ambitious task of defining criteria for the real worlds - the

narrative to unfold in the next chapter of this manuscript.

Back Home Next