1.1 SW Definition

The alien

Far away in the galaxy live aliens who believe in a multiverse. They believe there is an infinite number of worlds in

this multiverse and they live in one of those. These aliens can teleport themselves

from one world to another. The teleportation itself is easy - you study a life form from

another world, play as if you are that life form and at some point of time you

find yourself teleported to that world. At the destination point aliens take new form and

blend into environment. Everything happens naturally, with almost no extra effort required.

THe only problem they have at the new place is an amnesia caused by

the long-distance travel - they cannot remember exactly who they are or where they came from.

One of such aliens has teleported himself to the planet Earth - a ball made out of rocks and magma, covered

by thin layer of dirt, water, and gas and

flying in an empty cold space around the young, yellow star. The surface of the ball is teamed with various

life-forms. THe alien calls them shape-shifters. They grow into a certain shape by consuming and filtering elements

from the surrounding environment but after some time their bodies disintegrate into a bunch of atoms and molecules.

This basic material spreads all over the planet, to be mixed with other atoms and molecules,

and eventually to integrate into a

new shape, which reaches a certain size, and then disintegrates again spreading all around and the cycle

repeats again and again. They

bubble up and down into various shapes exchanging with each other basic materials.

They cannot live in an empty space,

the cannot travel across the galaxies. They are tightly integrated into the environment of this planet.

One of those shape-shifters (called humans) learned to transform simple abstractions into particular forms.

They can design and build dwellings, machines, social structures, and now regard themselves as a highly

advanced species, well above all other inhabitants of this planet

(even though they look and behave like monkeys - another class of shape-shifters).

THey have no idea how little they are, and how much there is still to be learned.

Anyway, now he is one of them. Consistent with the amnesia symptoms, he cannot remember anything about his past,

but feels he doesn't belong here and at some point in time will

have to move on. He has some vague recollections of the multiverse, the place he used to call home, but

these memories are so dim and uncertain he is not sure they are referring to

something real. He feels the notion of the multiverse must be important -

if it is not real,

he is stuck here, on this planet and can go neither back home nor move on exploring other worlds.

However the concept of the multiverse is hard to digest - you cannot believe something that does not make sense.

By the definition, the multiverse is made out of many other individual worlds and there are so many of these worlds,

some of them fake, others real,

and all of them claiming their own universal truth which is impossible to reconcile with the truth of others.

Technically speaking, you can combine all these contradictory worlds into a single big lump and call it a

multiverse, but then you will have hard time trying to convince yourself this lump represents something real.

And if you don't believe it is real, it will not work for you.

Despite all these problems, the alien is still hopeful he may get through. First of all, he needs to delineate

the real worlds from the fake ones. Once he has a collection of the real worlds established, he may refine them

further by cutting off sharp corners and fitting them into an overarching conceptual framework that would

integrate them into the multiverse.

To begin with, he collects information about this planet and its inhabitants.

He learns about particles and the void and the physical machinery of the universe from the textbook in physics.

The priest in the church tells him about the miracles and the divine nature of the human beings.

The old general talks about the friendship, honour, and duty.

Kids from the nearby school suggest to him to write a letter to Santa Clause – the guy is good with miracles

and may help him to get back home.

The alien, therefore, has to ascertain which of these stories are likely to be true and which of them are not.

He knows there is a common

knowledge shared among all communities, basic things such as not crossing the road when the light is

red (or else you get hit by car), wash your hands before lunch (or else you get sick),

if you drop something it will fall and so on. All these statements are likely to be

true.

But apart from such simple statements, every story makes certain claims which make them inconsistent with each other.

Some of these inconsistencies could be resolved by assuming

these stories to be complementary to each other and referring to different aspects of the same world. For instance, the

story of the general would fit both the world of the scientist and the world of the priest. But the story of the

scientist and the story of the priest are hardly complementary to each other and their reconciliation is not a

straightforward task. One of the key points of the controversy here is, for example, the concept of the human nature.

Both science and religion claim their exclusive authority and the rights to explain and manage this complex entity.

Both give drastically different accounts of the human being starting from the very definition,

to its origins and its purpose.

THey cannot be both true. Either one teaching or another must be false. To separate truth from the

counterfeit, the alien tests them through a number of check points such as, for example:

- The requirement of the self-consistent description of the world – the real world must be based on a more-or-less

coherent story. Neither of stories he has heard so far has been perfect, and each included a degree of inconsistency but

some of them were more coherent than others.

- Secondly, he tests these descriptions against empirical evidence, something that he can observe, measure and know

with a high degree of confidence. If a story says “there is an apple on the tree” but he cannot see it, then the story

is likely to be false.

- Thirdly, he has a time machine which accelerates time. Instead of spending ages practicing, for example, Buddhism, he

can test enlightenment in a matter of just a few hours.

If neither of these check-points provides conclusive answers, he subjects the story to further, less objective but still

useful tests, such as:

- Credibility of the source - a story told by a liar is unlikely to be true.

- Persistence through time also matters – a story and practices backed by historical records would be more believable

than a recent invention.

- Finally, he would put more trust in a story which is told and believed by a large community rather than that of a

small group of practitioners.

Ideally, he would seek black and white answers which clearly state false and true descriptions of the world. However,

he quickly realises that instead of having clear cut line separating the true

worlds from fairy tales he may end up with different degrees of plausibility.

Indeed, apart from some trivial cases, neither of the aforementioned check points, designed to filter out a

single truth, is capable of establishing a single true description of the universe.

The first check point, for example, fails because each description

tells a more or less coherent story but none of these stories is fully coherent, they all have some inconsistencies and

imperfections. As for the correspondence to empirical ¬evidence, the choice of the evidence is not unique and depends on

what people believe and what they practice. In other words, there are many different descriptions of the world, each of

these descriptions tells more-or-less coherent story and each of these descriptions is consistent with its own set of

empirical evidence. Experiments with a time machine show that individuals internalise beliefs and convictions of their

own culture. Referring to the source of knowledge, the persistence in time, and the community support criteria for the

belief network does not provide conclusive answers either.

The questionary

Despite discouraging first results, the alien determined to keep going. It is ok to have some inconsistencies between

established worlds. He may work out solutions later. But at this stage he still needs some rules to separate true

(or plausible) worlds from the pure fiction. And he knows there are fiction worlds, never to be considered real.

For example, the story of Santa Claus (SC) seems to be one of such fictions.

A number of arguments support this conclusion. Firstly, this story contradicts the common knowledge

of everyday experience. Whilst everyday experience may not be of a paramount significance in matters of establishing the

truth, the fact, for example, that no one has seen flying reindeer makes the whole story suspicious. Secondly, the story

contradicts the laws of physics (e.g. mass conservation, no action at the distance, finite speed of movement). Thirdly,

satellite images do not show any signs of SC at the North Pole. The video cameras he set during Christmas at random

locations around the globe have recorded multiple occasions of fraud - adults in the disguise of SC and pretending to be

SC. Based on all this evidence, he concludes with a high degree of confidence (but not 100%) that the story of SC is a

fake story. He was confused at first by a regular commotion occurring in certain societies during the Christmas period,

believing it to be a sign of some natural, objective phenomena, but then realised that all this was just a matter of

social conventions. When he cheated the villagers of one of the remote settlements by delaying Christmas for a day, no

one has noticed the trick thus conforming his hypothesis – the SC must be not real.

The situation becomes more delicate when it comes to discriminating between the worlds which adults believe to be true.

Ranking them in terms of their plausibility is not trivial. To begin with the alien decides to make an inventory

of such worlds, a short list, to have a closer look at them and see where they clash with each other and

how to fit them into the multiverse.

He makes up a short questionary which is meant to provide a brief overview of the key building

blocks of such worlds. In the disguise of a social scientist, he asks random people on streets to provide concise (less

than one-page) answers to the following questions

- What does this world consists of (ontology)?

- How does it work (cosmology)?

- Why does it work this way? (metaphysics)

- Who are you (identity)?

- What do you do (practices)?

- Why do you do it (values)?

- Metanarrative

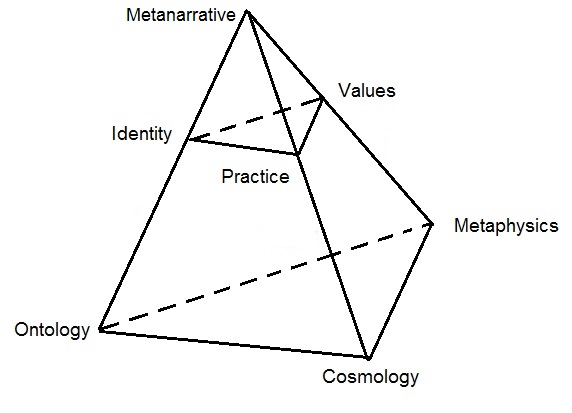

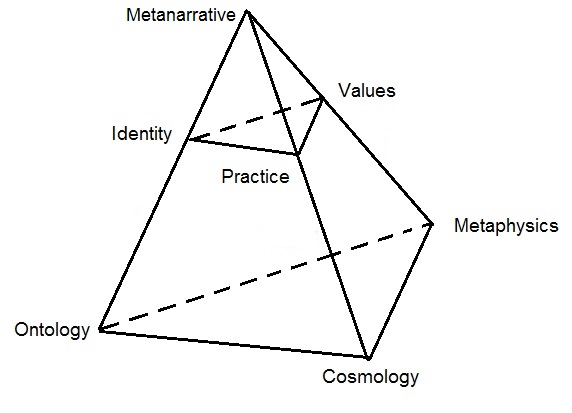

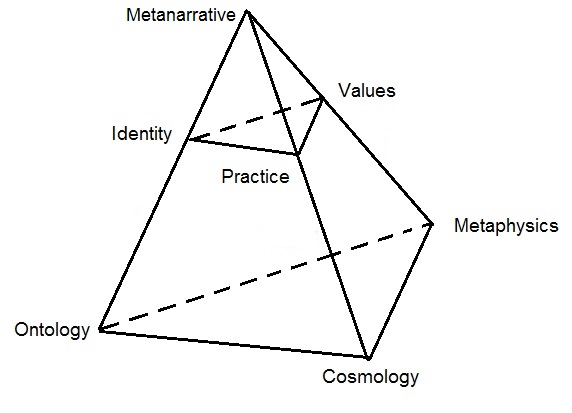

Figure 1.1 provides a schematic representation of this questionary.

Figure 1.1 Schematic representation of the questionary

The first question (concerning ontology) is about enumerating and explaining major building blocks of this universe.

Clearly, you

may not be able to give an exhaustive description here. Furthermore, the meaning of some items in this list will remain

obscure until explained later, in other sections of the questionary, through the reference to the functions of this item

in the whole structure of the universe. Even so, you can tell that the world of a scientist consists of atoms and voids,

while the world of the religious person comprises divine entities and miracles. The general may say that the world is

divisible by alliances and potential threats.

The next task (concerning cosmology) is to specify the environment where your story unfolds. The story is usually about

people who live in the evolving world. You tell your audience how the bits, you have introduced earlier in the first

part of the questionary (ontology) interact with each other and evolve through time.

The third question (about metaphysics), asks why did you choose this particular description of the universe rather than

some other?

These first three questions (about ontology, cosmology and metaphysics) are predominantly about the external world. The

next three questions (about identity, practice, and values) narrow down this questionary towards the description of

specifically human affairs.

The “Identity” question is about specifying a human nature (or stating that there is no such thing as a human nature).

The question about practices is to clarify what people in this universe do, and what they should or should not be doing.

The question of “Values” is about defining what is good and what is not-good. The body of the dry monochrome description

of the self and the universe in this section is dressed up into the colourful gown of moral sentiments and ethical

perspectives.

The last, seventh, section of this questionary is about a mertanarrative which integrates all the previous questions

into one comprehensive whole and tells a story about the self and the world. The questionary without metanarrative could

be a collection of fragmented stories, with minimal cohesion in between, and perhaps even some contradiction present.

The metanarrative unites these stories, brushes out obvious contradictions, and provides one out of many other possible

interpretations of the collection.

After giving it some thought, most people (except professional philosophers) are able to fill up this questionary and

provide a short narrative description of the universe and themselves. The philosophers become stuck on the first

question and do not make much progress on the rest. Non-philosophers are more productive. In general, texts they write

are more-or-less coherent, conveying some kind of a story. When it comes to details, however, all these stories are

vague and imprecise, often operating with poorly defined terms.

Our alien collects these stories into distinct classes representing communities of scientists, priests, warriors etc. He

suspects that these stories may represent parallel worlds which people either used to live or have some ability to

perceive. A collection of stories representing a particular world he calls a "Storied World" (SW).

Web-narrative

It is tempting to think of the metanarrative integrating the aforementioned questionary into a single story as the most

important, culminating point of the questionary. As if, one can discard all other questions and answers as soon as they

have contributed to the metanarrative description of the world. I believe, this perception is misleading. The collection

of stories created by people answering specific questions is not any less important than the metanarrative which

emanates from these stories. In fact, it might be more appropriate to think of the metanarrative as one of the stories

in the collection rather than a culminating, the final product of the questionary.

The collection of stories is not reducible to a single narrative for a number of reasons. First of all, there is no

one-to-one correspondence between the questionary and the metanarrative and, having a collection of stories as a

background material, one may devise different metanarratives from this collection. One single metanarrative does not

provide complete account of all stories generated by the questionary. Discarding the questionary after having completed

the metanarrative, would lead to a dramatic loss of information. Imagine substituting all science literature including

papers by different schools of scientific thought with a single story about the science which does not consider rival

theories and hypothesis.

Secondly, the collection of stories associated with this questionary represents a dynamic body of knowledge which can

grow and evolve with time in many different shapes and directions. A single story or a metanarrative is essentially a

complete and static entity. It has the beginning, the body, and the conclusion.

It documents biographies that start at the birth

date (introduction), follow through the life time (the main body), and finish with the grave tomb (conclusion). A sequel

will undoubtedly be a story about someone else; the original main hero is dead. Conversely, the collection of stories

derived from the questionary is always open ended, because it is never complete, and can grow forever. Background

materials set by the previous authors provide some channelling for new developments, but the whole structure is so rich

and multifaceted that can easily accommodate fundamentally new stories.

Each question of this questionary does not specify a clear cut, isolated area of the enquiry. Instead, answers to

different questions are likely to overlap with each other. For instance, in some stories (e.g. Buddhism) cosmology and

psychology are so tightly entangled it is near impossible to draw a line separating one from another. Subsequently, the

description of cosmology is incomplete unless you provide some details concerning psychology and vice versa to explain

psychology one has to elucidate cosmology. To make these descriptions meaningful, you will have to either integrate them

into a single narrative (that would filter out major inconsistencies) or, alternatively, leave them separate but still

tentatively connected by the fact of their belonging to the same collection of stories.

Unlike a narrative structure, the collection of stories does not have to be self-consistent.

Different narratives in this

collection may tell different, contradicting each other stories. Because of these contradictions,

the whole body of knowledge based on these stories is more flexible and suitable for new developments.

The Vedas, Buddist texts, the Bible, and science literature exemplify such collections of stories. These stories can

be maintained and transmitted orally from

one generation to another, they can be written on a paper, or stored on the Internet.

Regardless of the form of their expression, they are irreducible in a sense that

no one single story (e.g. metanarrative) gives a complete account of the whole subject.

There might be a lot of redundancy

present in these stories conducive to contradictions.

There is typically no single author but many. The story writing

can take ages (hundreds and thousands of years).

A feature characteristic of such a collection of stories is its conceptual completeness in a sense that it must have

resources to accommodate and evaluate the truth value of any statement. Any enquiry about the self and the universe must

receive a proper handling within this structure. Not all questions will be answered, but the critical point is that this

collection must provide a conceptual background which makes it possible to handle every question whatever vocabulary is

used to formulate it.

The size and completeness of that collection could vary with time. The volume of scientific knowledge, for instance,

today is much bigger than that a few hundred years ago. How much of this knowledge is internalised by a particular

person varies from one individual to another and within a single individual at different stages of his life.

On the method

Because of the all-inclusive nature of the Storied World, the method of dealing with such a complete body of

knowledge has some

peculiarities. According to scientific method, you formulate a hypothesis, test it against established knowledge and

then depending on the outcomes of that test either accept or reject that hypothesis. In our all–inclusive collection of

stories the body of the hypothesis comprises the whole world, and hence no knowledge is left beyond that body to test it

against. In other words, there is no such thing as established knowledge residing beyond that storied-world (which itself is our

hypothesis), and if one storied-world contradicts another, there is no reference point beyond the body of the hypothesis

to establish its truth value. Unless, of course, we are prepared to postulate some privileged knowledge and methods of

dealing with such knowledge. And if we do, these privileged methods and knowledge,

once established, must be taken for granted and never questioned afterwards.

Consider as an example the story of the “Big-Bang”. According to many religious teachings

this story does not make sense. On the other hand, it makes perfect sense within the scientific interpretation.

In either case the truth value of that story is assessed against a larger body of knowledge formed by a particular SW.

To assess the truth value of different stories from the vantage point of some “impartial” observer (not

attached to any particular SW), this observer would have to step outside of every possible SW.

However, no Storied World implies no language and, hence, no principles whatsoever to guide our decisions.

If we don’t want to succumb to the existential vacuum here, we have to postulate rules, perhaps, grounded

into some minimalistic collection of stories, upfront. These rules are needed to provide us criteria to rank other

stories (see Gadamer’s “Truth and Method” for in depth analysis of this subject).

So, what kind of rules we may implement in order to evaluate different storied-worlds?

To start with, we may require Storied Worlds to be represented by self-consistent collection of stories (otherwise

we may not be able to comprehend them). It would be nice also for these stories to be consistent with an empirical

evidence (so that we can verify them through practice).

We may want also to add rules pertaining to ethical principles, or referring to our quality of life,

or the notion of sacred, etc. A complete collection of such rules shall provide criteria to rank existing

storied-worlds. The same rules would be used to channel the development of new storied-worlds (by imposing

constraints on the kind of the worlds we can to create).

Why did I choose this particular set of rules rather than some other set?

I can explain it with the reference to some aesthetic considerations or quote an “unreasonable efficiency” of the

logically-consistent bodies of knowledge or highlight the quality of life and importance of human beings.

But then other people may argue that we

shall consider only those stories and rules which promote the well-being of cats, because cats are important and

this fundamental truth is hardwired into the human nature and they can feel it etc.

It is very hard to argue with a human nature. To save time and energy, I just cut it out here and postulate the

aforementioned principles guiding the development of new

stories. I believe, these principles are sufficiently general to let us analyse and develop a rich variety of new SWs, on

the one hand, and, at the same time they are sufficiently constraining to cut out unwanted entries. We will elaborate

further on these principles through chapters 1 to 3 to make them more structured and convincing.

The critical point to remember,

however, is that the rationale behind them is never watertight. There is always place for an alternative set of rules

that would provide other means for ranking different storied-worlds. On the other hand, the choice is never completely

arbitrary. To be sustainable, a SW must respect at least some norms of ethics and be consistent with the laws of

physics. In other words, vocabularies do not exhaust the whole world. There are practices and experiences that transcend

stories and open the door towards other realities in our lives which surpass linguistics and may provide extra anchoring

points to justify our vocabularies.

Contradictions

Both people and aliens like to communicate their stories in a self-consistent coherent form.

Such stories narrow down the manifold of possible interpretations to a very specific one, we tend to call truth.

In a self-consistent story, humans and aliens start from the same premises and arrive to the same conclusions.

From the management perspective having one single description of the world helps a manager to decide the best

course of actions. Coherent stories also help people to communicate with each other - if a story is

inconsistent we often say it does not make sense.

Yet, stories we tell about ourselves and the world around us are often infested with contradictions. The degree of

the logical cohesion present in these stories and the attitude towards contradictions varies from one storied-world to

another. In some teachings (e.g. science) contradictions are introduced pests to be eradicated - the smaller the

number of contradictions the better the theory. On the other hand, in many religious schools (e.g. Zen Buddhism,

Taoism), a contradiction is a critical and irreducible part of the teaching - get rid of all contradictions

and the teaching is gone.

The exact meaning of the word contradiction depends on the context. It could be referring to

contradictions between two statements (e.g. one statement saying “this is

white”, and another statement saying “this is black”), contradictions between theory and experimental evidence (theory

says “this is white”, but we can see it is black), contradictions between intentions and reality (he wants to maintain

healthy life-style but smokes), contradictory psychological states (love and hate the same person),

contradictions in social life (individual vs collective goods) etcetera.

The ubiquitous nature of contradictions in our lives has been expressed by Paulo Coelho -

“we are in such a hurry to grow up, and then we long for our lost childhood. We make ourselves ill earning

money, and then spend all our money on getting well again. We think so much about the future that we neglect the

present, and thus experience neither the present nor the future. We live as if we were never going to die and die as if

we had never lived.”

Our major focus in the next chapter will be on contradictions in stories we tell about ourselves and the external world.

A succinct definition that would serve our purpose reads: two statements are contradictory if we cannot believe in both.

The point I shall illustrate is that all established Storied Worlds have some degree of logical cohesion

and structure present, but neither of them is perfect - there are logical inconsistencies present in all of them.

Furthermore, these contradictions often represent critical and irreducible parts of the story line.

Back Home Next