3.2 Instantiated Storied-Object (ISO) Machinery

ISO Machinery

According to our definition of a real entity, if we can develop a logically cohesive description of something and

establish reproducible practices that demonstrate its characteristic features, then whatever entity we've designed it must be

real. This understanding provides a framework for creating and sustaining new real entities. The process

involves three steps:

- Design a logically cohesive description of an entity

-

Implement that design through practice

-

Test and maintain the implemented instance

The first step (Design) provides a general description of the entity to be created including outline of features

characteristic of it, and specification of reproducible practices one must follow in order to recover these features.

This step may also involve research and review of earlier studies relevant to the subject matter.

Implementation

step instantiates that design by following procedures which are meant to recover features characteristic of it.

This step transforms a theoretical construct into observable entity.

Finally,

the 3rd step is to test and either evolve it through time or just maintain it in a certain

state. The operation and maintenance manual required for this step must be available from the step one.

To facilitate this discussion, im going to introduce a couple of new terms:

- Storied-Object (SO): This term refers to the logically cohesive description of an entity. A storied-object

generalizes the concept of a storied-world, indicating that while all storied-worlds are storied-objects, not all

storied-objects are storied-worlds. This broadens the application of our framework to encompass a wider variety of

entities.

-

Instantiated Storied-Object (ISO): This is the outcome of the implementation step, where the storied-object is

brought into existence through specific practices that reproduce its defining features.

With these definitions in place, the process for creating and maintaining a new real entity can be succinctly rephrased

as follows:

-

Design a Storied-Object (SO): Develop a detailed and logically cohesive description of the entity. This

description should cover all characteristic features and include a set of reproducible practices necessary to instantiate

these features.

-

Instantiate a Storied-Object (ISO): Follow the reproducible practices to create

a functional instance of the entity.

-

Test and Maintain the Instantiated Storied-Object (ISO): Conduct tests to confirm that the instantiated

storied-object aligns with its intended design and functions as expected. Continue to maintain or adapt the instantiated

object over time to ensure its ongoing viability and relevance.

The schema of Design, Instantiate, and Maintain, which I shall henceforth refer to as the Instantiated Storied Object

(ISO) machinery, offers a versatile approach to creating and maintaining various entities, ranging from physical devices

to social constructs and even metaphysical concepts. The underlying strategy remains consistent across different

domains: develop a quasi-coherent description of the object, identify its key features, and implement reproducible

practices to verify whether these features are delivered.

For instance, consider the concept of a family. We understand what constitutes a family, including the

roles played by its members. By embodying these roles and engaging in familial practices, individuals instantiate the

corresponding storied-object — the family itself.

Similarly, martial arts provide another example of this process, integrating physical practices with intricate teachings

about human nature. Through training and adherence to martial arts principles, practitioners bring the

storied-object of martial arts into existence.

Religious rituals and scientific experiments also exemplify this approach, wherein there are precise linkages between

theoretical frameworks and practical applications, with specific outcomes expected from these practices.

In each case, the ISO machinery facilitates the creation and maintenance of entities by bridging the gap between

conceptual descriptions and particular instances.

Generalised ISO (GISO) Machinery

The ISO machinery offers insight into how we create artificial objects, from physical things like bridges and machines to

abstract concepts like social norms and laws. Design, implement, and maintain — this straightforward process has been

utilized by humankind for thousands of years to construct cities, establish policies, and build civilizations.

However, this approach doesn't apply to natural systems. Natural phenomena such as stars, oceans, and mountains seem to

exist independently of human intervention. We don't design or bring them into existence; they exist because

of some processes evolving by themselves (and some of them happening even prior to the appearance of humans). This

suggests a significant distinction between natural and artificial systems.

Does this distinction matter for our project of creating new artificial worlds?

I think, it does. The distinction between natural and artificial systems is indeed significant. While we may prioritize

psychological, ethical, and metaphysical realms, valuing concepts like the meaning of life, love, and goodness, we must

also acknowledge our interest in understanding the broader natural world. Even as we create new artificial worlds by

reshuffling social and ethical norms, we can't disregard the importance of natural phenomena.

Without a framework encompassing both natural and artificial domains, there's a risk of perceiving artificial

systems, particularly those rooted in social conventions, as somehow inferior or less authentic than natural ones. This

perception will cast doubt on our discussions about social, ethical and metaphysical domains, as anything

beyond the natural realm might be seen as less reliable or deficient simply because it's human-made.

To truly advance our project of creating new artificial worlds, we need to extend the ISO machinery to encompass both

natural and artificial realms. This will require further refinement of our assumptions about how the ISO machinery

operates, ensuring its applicability across various domains.

The structure of the multiverse

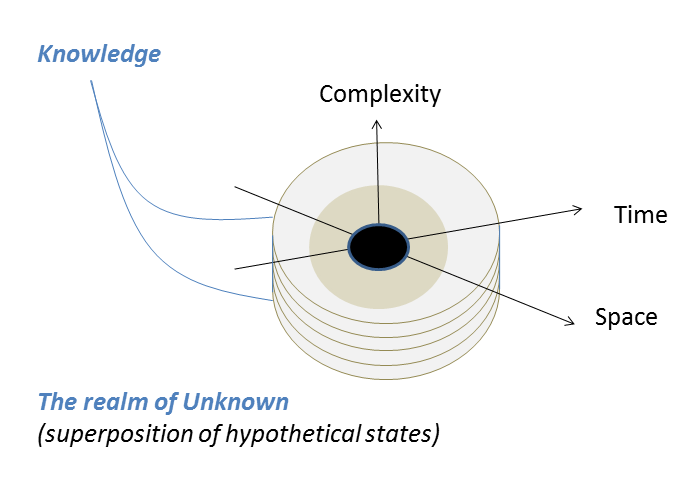

To begin with, let's introduce three ontologically distinct realms,

each playing a vital role in the creation and maintenance of new entities via ISO machinery (fig. 3.1):

-

Abstract Realm: At the top level, we find the realm of abstract entities, which includes all storied-objects.

This realm encompasses every conceivable story, whether told or untold, authored by anyone, and spanning various types,

from established mathematical theories to laws of science. While storied-worlds are a prominent example, there are

countless other storied-objects within this realm, many of which remain unknown to us.

-

Human Realm: The second level consists of human beings, who serve as the means to instantiate particular

storied-objects out of their abstract counterparts. Humans are special entities, which belong to both

abstract and particular realms. To address potential identity paradoxes, we posit that each person possesses an essence

defining their identity, and

tethered to a specific storied-world.

-

Particular Realm: Finally, the third level comprises the realm of particulars — the instantiated storied-objects

themselves. Particulars are classified into three groups: entities binding to all people (universal entities), entities

binding to a specific community, and private entities unique to individuals.

This hierarchical structure delineates the progression from abstract concepts to instantiated realities, with humans

serving as the conduit for bringing storied-objects into existence within the particular realm.

Figure 3.1. Schematic representation of the ontology underpinning ISO machinery

Private entities (figure 3.1) represent our thoughts, feelings, and other idiosyncratic experiences. Others do not have

immediate access to these experiences, but we can communicate them via particulars shared either within a community or

by everyone.

Entities shared by a group, such as customs, laws, and religious beliefs, are based on societal norms and established

practices that support their development and maintenance. The notion that individuals contribute to the creation and

maintenance of these entities is widely accepted and uncontroversial. To fully participate in these shared constructs,

members of the community usually need specific education or training enabling them to understand and embody their

unique features.

Entities shared by everyone include natural systems and the laws of physics. These are generally seen as existing

independently in nature, waiting to be discovered rather than created by humans. Apart from specific exceptions, such as

scientific experiments, people naturally possess the ability to perceive these systems without needing special education

or training to make observations.

We are aware of the existence of particular entities through observations, measurements, and other structured

practices that provide empirical evidence. This evidence can often be universally accessible because it relies on the

basic biological, physical, and psychological traits shared by all humans. For example, no special training is required

to see an apple, taste it, or feel its texture.

However, some empirical evidence is unique to particular communities and requires special education or training.

Members of these groups need to follow detailed instructions to achieve outcomes like experiencing a certain

psychological state, developing a particular character type, interpreting philosophical concepts or conducting and understanding

scientific experiments.

In the abstract realm of stories, there is an infinite number of storied-objects. Some of them we create ourselves

through the creative writing. Whether we are truly creating something entirely new that never existed before, or merely

discovering something that already exists within this abstract realm, is, in my view, inconsequential. Choosing to view

it as creation or discovery is largely a matter of personal preference.

We are capable of creating stories that make no sense, as well as crafting narratives that are logically cohesive but

offer no guidance or actionable instructions. From the ISO perspective, these narratives are considered "dead scripts" —

they are irrelevant to our lives. We shall leave such stories aside and focus instead on those that promise tangible

outcomes and offer reproducible practices to test these promises.

According to the ISO framework, humans are special - they are capable of instantiating particulars out of their

abstract counterparts. For example, by following a set of instructions, we can assemble a bicycle from its parts. Similarly, by

performing a play-script, we can embody the character type of a samurai. This process of the instantiation

draws on parallels with the object-oriented programming: think of a storied-object as a class, and a human,

through specific practices, as instantiating that class into a particular object.

All this is fine, yet the question of how to bring natural systems into existence via ISO machinery remains.

To address this question, we introduce further

assumptions concerning the nature of our knowledge and the cycling between abstract and particular realms. We

suggest that acquiring new knowledge through observation is equivalent to instantiating a particular entity out of its

abstract counterpart (i.e. out of storied-object). Conversely, if all collective human knowledge about a particular entity is lost,

that entity reverts to its abstract state. The following section provides a more detailed explanation of this perspective.

The cycling of the multiverse - Epistemological turn

In this section, we shift our focus to an epistemological perspective, examining our knowledge of storied-objects rather

than the storied-objects themselves.

The line between the ontology and epistemology talks, I think, is very slim. One might argue that

only knowledge matters and the ontology talk is just another way of expressing that knowledge. Alternatively, one

could claim that ontology comes first, and the knowledge builds on top of it. I think, either of these interpretations

will do the job.

Both perspectives are valid, but for the purposes of enhancing the ISO framework, especially in relation to natural

systems, I think, the language of epistemology is more convenient to utilize.

Epistemological view allows us to build on the normative component of the definition of knowledge to produce new

interesting interpretations of storied-objects. For example, we can reverse the ordering of the cause and effect

relations and instead of saying that we have empirical knowledge (i.e. knowledge derived from observations) of only

those things which exist, claim that only those things exist that we know about. The knowledge comes first, the

existential status follows. Conversely, if we (all people) do not have empirical knowledge of something, then that

something does not exist in a particular form. Furthermore, if the knowledge of the particular entity is lost completely

(so that no one in the whole world holds this knowledge anymore) then the corresponding entity transforms from

the particular form

into the abstract form. Terms “we” and “us” here refer to all humankind considered a collective entity

(a repository of all knowledge accumulated up to date) rather than to separate individuals.

Acquiring new knowledge is now equated with bringing a new entity into existence, and conversely, losing this knowledge

causes the entity to revert to an abstract state. This assumption establishes a closed

loop between the abstract and particular domains, enabling a cycling of entities between these two realms

mediated by human practices.

From this epistemological perspective any unobserved and hence unknown (to humankind) natural object does

not exist in a particular form. Instead this object exists in the form of a superposition of abstract hypothetical

states. By following certain procedures (called an observation, or measurement etc.), we instantiate one of these

abstract hypothetical states turning an abstract hypothetical entity into a specific particular object.

Observing a new planet now is analogous to assembling a new lawn mower – both processes involve following a set of procedures

(rules of observational experiment or instructions of the user-manual) to achieve an outcome

(having observed the planet or having assembled the lawn-mower).

It may seem that there is still a stark difference between the unpredictable discovery of the planet and the predictable

assembly of the lawn mower. However, this distinction mainly arises from the differing levels of prior knowledge we

assume implicitly for these two scenarios. For a lawn mower, we assume upfront the right set of spare parts and

the right instructions which narrows down the set of possible outcomes.

In contrast, discovering a new planet involves broader, less defined expectations based on our

limited prior knowledge, a topic we'll delve deeper into later (when discussing the ordering constraint).

The behavior and parameters of this planet will be consistent with the established laws of nature, as these laws

were instantiated earlier, and for a new observation to be consistent with the established body of knowledge

it must obey established laws of nature. This newly instantiated

planet continues to exist as long as anyone in the world is aware of its existence or as long as there is a supporting

circumstantial evidence. However, if all knowledge of this planet is entirely erased—leaving no one in the world

is aware of its existence — the planet

reverts to a state of superposition of various celestial bodies. Under these conditions, if a different observer were to examine the same location,

they might identify a star where the planet was once observed. No contradiction would arise from this new finding, as

all memory of the planet would have vanished.

Note that this perspective does not conflict with the natural sciences, as science primarily concerns itself with the established

natural objects, not their metaphysical origins. Furthermore, this vision

can be refined further to address and resolve logical contradictions. We will explore these

refinements and address these issues in further detail later.

Why do we care introducing this interpretation?

THe original intention was to elevate the significance of

socially constructed entities such as virtues, customs, human nature, gods, afterlife etc. Instead, rather

than elevating the significance of these social constructs, our perspective demotes

the status of natural objects by making their existence

dependent on human awareness, thus aligning them more closely with social constructs.

By applying the same principles to the cycling of natural and artificial systems across abstract and particulate domains,

we can now justifiably consider both natural and artificial systems as 'real'.

The remainder of this chapter will further elaborate on this

perspective, detailing how it reshapes our understanding of reality.

The knowledge ball (k-ball)

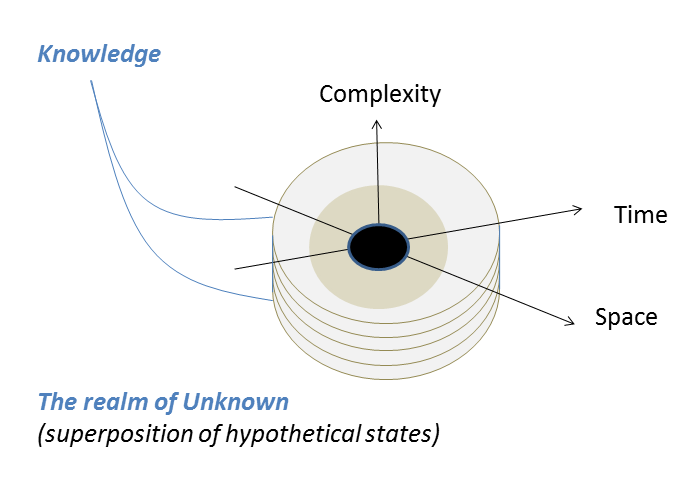

To illustrate this epistemological approach, let me introduce the concept of the

knowledge ball (k-ball). The k-ball symbolizes all the knowledge about the instantiated world that is currently

accumulated and collectively maintained by humankind (figure 3.2). This body of knowledge is based on

empirical evidence and is distinct from our understanding of abstract forms.

Following the categorization from the previous section, we differentiate three classes of this knowledge: knowledge

shared by all people (represented by the dark area in figure 3.2), knowledge shared by communities (the grey area), and

private knowledge (the encircled white area). Outside the k-ball lies the realm of abstract entities, including

storied-objects that represent hypothetical states of the system.

Fig 3.2 The knowledge ball (k-ball)

It's easy to see that the knowledge ball (k-ball) is simply another way to visualize the schema presented in figure 3.1. By

rotating the individual columns from schema 3.1 and stacking them, we can transform figure 3.1 into figure 3.2.

The primary reason for introducing this new representation is its ability to more effectively illustrate features

specific to our collective knowledge.

The k-ball is a dynamic entity that evolves over time. As new objects are conceptualized from abstract states, the

corresponding knowledge is accumulated and incorporated into the existing collective knowledge, causing the k-ball to

expand. Conversely, if established knowledge isn't consistently reinforced, it starts to degrade and can eventually

disappear entirely. When this happens, the associated objects revert to a superpositional, abstract state. This erosion

of knowledge creates a porous k-ball, where certain ideas that were previously justified may no longer be substantiated,

yet they continue to be considered as knowledge. This process, referred to as the "sedimentation of knowledge" (Berger)

highlights how knowledge can persist in a less substantiated form.

The concept of the k-ball can be compared to a termite mound, which is constructed through the collective efforts of the

entire termite community. Each termite contributes to the mound by adding construction material, and this

allows the mound to expand. However, this structure is also continuously

subject to erosion; environmental factors gradually wear it down until parts of it turn to dust and disappear.

Our knowledge is inherently imperfect and always carries some degree of uncertainty. The knowledge ball is

anchored in the present, reflecting our inability to predict the distant future or fully understand the distant past.

One of the causes for this limitation stems from the fact that all our empirical knowledge is based on induction, which is

unreliable for long-term forecasts.

Similarly, our knowledge is spatially concentrated around the scale of objects visible to the naked eye. We struggle to

comprehend phenomena at extremely large or minuscule scales due to a lack of empirical evidence in these areas.

Additionally, our understanding of complex systems is limited; we lack a unified description for them. As we move

further from the center of the k-ball—our core area of reliable knowledge—the uncertainty of our understanding

increases, and our knowledge becomes more abstract and hypothetical.

Instantiation of physics: The ordering constraint

The "ordering constraint" underlines a fundamental rule of the GISO machinery: the first instance rules.

According to GISO, everything in this universe all the oceans, mountains, and stars, are brought into existence through

specific actions we undertake, known as observations

or measurements. The result of these actions materializes as an instance of the corresponding storied-object.

Once created, these instances persist, continuously

contributing to the growing collection of socially produced and maintained empirical evidence, much like individual

termites building a mound by adding patches of dirt.

To maintain consistency among instances created by different people, it is vital to produce these objects

for any given spatial location sequentially,

one at a time. This approach prevents conflicts between new instances and those already established. For example, if I

discover a star at a specific point in the universe, another person, unaware of my discovery, should not later be able

to declare a black hole in the same spot (especially if the star is nowhere near becoming a black hole).

The "ordering constraint" ensures that the first established instance fills the gap in our knowledge with new information and

that information stays. This rule is crucial for

keeping our collective empirical knowledge coherent and consistent. It protects the integrity and reliability of the

knowledge shared by humanity.

To clarify, when I first observe a new star, I'm not just capturing a snapshot of that star at a single moment. Rather,

I'm instantiating its existence across a four-dimensional space-time continuum. This continuum centers on the present

but stretches into both the future and the past. This 4d instantiation explains why subsequent observers cannot

simply spot another object in the same location later.

To further illustrate the evolving four-dimensional nature of instantiated objects, consider a planet

orbiting the star we've observed. Let's say the planet was spotted at location A yesterday. Today, another observer

finds it at a different location, B. According to the ordering constraint, even though no previous observations were

made at spot B, and today’s observation is the first observation ever made at that location, the new observer is still

expected to find the same

planet there. This is because any other finding at the location B would conflict

with the earlier observation at the location A.

This requirement reflects the cause and effect relationships dictated by the laws of physics, which span the entire

universe. These laws ensure that the ordering constraint acknowledges the correlations between events that are distant

both spatially and temporally. Thus, the current state of a specific volume of space may be influenced by past events

that occurred elsewhere. In other words, the description of the universe must be based on a more or less coherent story.

While cause-and-effect relationships are crucial for understanding the universe, their role should not be overstated. In

nature, there are chaotic systems that disrupt these linkages, making it difficult to predict distant future.

This uncertainty weakens the effectiveness of the ordering constraint.

Examples

Laws of nature

From the GISO perspective it seems we must be able from time to time to discover (instantiate) solar systems with the

altered laws of physics (analogous to random initial state), but for some reasons we don’t.

Unlike the location of newly

discovered planets, varying from one place to another, the same laws of physics seem to apply across the whole universe.

Indeed if we assume a piecemeal approach, discovering new solar systems here and there, one at a time,

at some point we may run in a solar system with an altered laws of physics.

However, the science always tends to generalise by trying to figure out (or guess) the fundamental principles

behind particular phenomena and then rolling it out globally to test across the scales. As soon as the physicists have

built and simulated cosmological models simulating the whole universe (and tested it against observations),

the manifold of hypothesis has collapsed

into the universe with the uniform distribution of the laws of physics. As any inference based on induction,

this conclusion is still not watertight but any new observation contradicting to this accumulated knowledge

would require an explanation - why this new observations does not agree with the model and historical data.

Vikings and magnetic fields

Vikings knew nothing about magnetic fields and Maxwell equations. And yet, they used magnetic objects to guide their

ships across the seas. Perhaps, they thought of it as a magic.

Since GISO claims knowledge = reality, and vikings did not know about magnetic fields,

does it mean there was no magnetic field during the time of Vikings?

THe short answer to this question is it does not. According to GISO, vikings using magnetic materials in navigation,

counts as an empirical evidence indicative of the magnetic fields (even though they called it magic). Later on when

Maxwell has formulated his famous equations, and the use of electro-magnetic appliances has become ubiquitous,

these evidence became overwhelming (and magnetic fields fully instantiated).

Evolving histories

History is a narrative we construct about our past, using the knowledge we have at present.

According to the GISO machinery, history evolves over time. As new evidence comes to light, the history is updated;

the original version of it fades away into an abstract domain, and a new, history consistent with a new data takes shape.

Since different cultures have various beliefs that they regard as knowledge, people often base their historical

narratives on

differing sets of information. This phenomenon can lead to multiple histories of the same

objects or events contradicting each other(such as the planet Earth, for example, having different age in different histories).

Having conflicting histories presents a real challenge.

The simplest solution here is to claim one history to be true and other histories false.

Having said this, another interesting opportunity we can entertain here is to claim two conflicting histories

true as long as no contradiction arising from this claim can be proven. For example, there is a tribe A inhabiting

the north pole and claiming the Earth to be 4 billion years old.

Another tribe (B) lives on the south pole and claims the Earth is one thousand years old. As long as tribe A and tribe B,

are kept isolated from each other

and unaware of the rival histories, and as long as there is no other observer following this story to claim a

contradiction, both histories remain valid. Eventually

these tribes either diverge into two distinct universes (one with old Earth and another with the young Earth),

or else they meet each other and in this case they will have to reconcile their histories.

The GISO framework provides a unique perspective on the history of the universe before the emergence of humans. According

to this view, such a history didn't actually exist until humans came along and instantiated it through their

observations and narratives. In other words, history as we understand it began to be shaped and defined only when there

were humans to create and interpret the records of past events. Our ancestors, isolated tribes of the cavemen,

may have entertained different

sorts of histories. To avoid a contradiction, we must either assume multiple universes spawned by these tribes

(each universe having its own history), or consider these tribes meeting each other and reconciling their stories.

History isn't fixed and immutable but can be shaped and even altered, depending on new

interpretations and evidence brought forth by human inquiry. This concept allows for the possibility that

historical events can change significantly as new information is discovered and as new perspectives are

developed. Thus, history, under the GISO model, is seen as a dynamic construct, continuously evolving as humans learn and

reinterpret their past.

What is up to us to reconcile?

I can follow instructions in user-manual to assemble a lawn-mower or a tractor out of parts.

The decision to build a lawn-mover or a tractor or both is mine.

Analogously, I can practice buddhism, bushido, or science to become a buddhist, a samurai, or an atheist.

The decision is again mine.

What about the star in the sky? Say, I have a telescope to observe a particular region of the sky. I am not

sure there is a red star at that location. Is it up to me to decide on the outcomes of my observation upfront,

prior to observation, similar to the case of assembling a lawn-mower?

This question introduces two contrasting views. The traditional view suggests that the star, whether it exists or not,

is part of a real and independent world of particles, which conforms to the laws of physics and is unaffected by our desires.

On the other hand, the GISO framework

offers a different perspective. It suggests that before observation, the star's existence is just one possibility

among many.

When we observe that star for the first time, we choose from these possibilities, solidifying one reality where the

star exists. This

action collapses all other potential states into the one we observe, similar to how quantum mechanics describes

particles in superposition existing in many states until observed.

Still, even from the GISO perspective there seems to be a fundamental difference between the discovery

of the star (highly uncertain endeavour)

and assembling a bicycle or practicing Buddhism (which seem to be within our control).

I'd argue this stark distinction blurs upon closer examination.

The confusion stems from not distinguishing

between our ability to plan for the future and the actual unfolding of events.

It's true that we can choose whether to search for a star or try to build a tractor. These are decisions within our

control. However, the outcomes of these actions (actually finding that star or successfully building the tractor) are not

guaranteed. Various factors beyond our control can affect the results, despite our best intentions.

Example with the lawn-mover, presumes that all necessary components are present and correct,

effectively predetermining the result—a fully functional lawn-mover. This is akin to assuming that all elements necessary

for the existence of a star are already in place in a given region of space, ensuring its observation.

To draw a more accurate comparison between these scenarios, consider a situation where you possess a mixed assortment of

parts without clear indications that they can be assembled into a lawn-mover. Here, the decision to follow the lawn-mover's

assembly manual is a gamble, akin to the uncertainty faced when scanning the heavens for a star. In both cases, the

initial conditions are not fully known, and the choices made may not lead to the expected results.

In the same way, we can decide to practice Buddhism, but whether we truly embody its teachings and become a Buddhist

depends on factors that aren't entirely under our control. It's important to recognize this distinction: while we can

choose our actions, we can't always control the results. This understanding helps clarify that the process of finding

stars, assembling lawn-movers, or adopting a religion belief follows a similar pattern — we can set out on a path, but we can't always

predict where it will lead. We can plan the future but it is not up to us to decide whether this future materializes.

I'm actually relieved that we can't just instantiate anything we want at will. If that were the case, we'd be trapped in

a limited world defined solely by our current language and understanding, which is always finite. The whole idea behind

adopting practices and exploring different paths is to break free from these confines and allow new experiences and

ideas to enter. Our multiverse would indeed be dull if it were all predetermined. The freedom to choose our path

enriches our lives with endless possibilities, and the uncertainty of not knowing exactly where we'll end up makes our

journey through life all the more thrilling.

Annihilating Past Events

Is it feasible to reverse or "un-instantiate" events from the past, such as erasing the existence of a previously

observed star or a constructed tractor? Note that this question extends beyond the physical dismantling of these objects to the

deeper inquiry of whether we can make it as though these events never occurred at all.

Consider the idea of completely eliminating all knowledge related to an event. Imagine placing a cat in a box and then

removing every trace of the cat's presence and the act of placing it there, including any indirect evidence.

Theoretically, if every piece of evidence were perfectly erased, upon reopening the box, something entirely unexpected,

like a rabbit, might appear instead of the cat.

This concept suggests that altering the past could be conceivable if we could erase all knowledge of an event. Beware,

this theory is fundamentally untestable because it relies on the total and successful elimination of all evidence. If

any evidence to the contrary is found, such as the original cat appearing when a rabbit was expected, the theory

defensively argues that the evidence clearance wasn't comprehensive. In this way, the theory protects itself from

disproof by claiming that any evidence of its failure simply proves that its requirements weren't fully met. This setup

makes the theory invulnerable to conventional disproval, framing any potential contradictions as failures of execution

rather than flaws in the theory itself.

Summarizing the Concept of Instantiation in Physics

Let's summarise how we bring physical objects into existence, or "instantiate" them. The

central idea is that if there are multiple interpretations or hypotheses about an entity, and each one aligns with

established knowledge and is logically self-consistent, then each hypothesis is a potential reality for that entity.

Essentially, until

these hypotheses are tested, the entity exists in a state of superposition—comprising all these hypotheses.

When we observe or test these hypotheses for the first time, without prior claims from others influencing our knowledge,

this superposition collapses. This collapse results in a specific instance of the entity, providing empirical evidence

of its existence. Once instantiated, this object follows the laws of physics, which apply universally.

If the object has already been discovered earlier, any new observations must align with the instance

previously created. Over time, as empirical evidence fades away, the instantiated object can revert to a

superpositional state.

It could be hard to believe that everything we can see is instantiated by people. The mountains, and the seas, and

houses, and the stars and the galaxies. And yet, according to the GISO machinery, there is no contradiction in this

assumption. Imagine a mountain in a specific location that no one has ever seen. Prior to observing that location,

you could hypothesize several possibilities for the objects located at that spot:

a large mountain, a small one, a flat valley, or even a lake. Each of these hypotheses presents a feasible

scenario. When you visit this location and observe the spot for the first time, you solidify one of these possibilities into

reality. It’s possible the reality you encounter isn't what you expected — for instance, you might find a desert if you

hadn’t considered that option in your hypotheses.

Once observed, this mountain (or desert) joins the collective empirical evidence accumulated by humanity over history.

It becomes part of the shared reality. Therefore, the next time someone visits that spot, they will encounter the

mountain as it was observed, assuming no significant time has elapsed to erase all evidence of its existence. This

concept illustrates how our observations lock phenomena into the collective understanding of reality, shaping the

physical world we perceive. No contradiction to logic is encountered during such instantiation.

GISO and AI robots

It's fascinating to consider the idea that non-human agents like AI and robots could potentially create physical

objects simply by observing them or taking a photograph. We already know robots are capable

of assembling complex machinery like tractors, but can they create from scratch something

as grand as a new star or a divine entity?

One line of reasoning here is that satellites can take pictures of the Earth, but ist is only when humans observe

these images that the objects are instantiated.

Another perspective is that Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) are just better versions of our brains. Since the knowledge

is distributed and equated to the reality, AI must be able to instantiate as much as we can and even better.

A third viewpoint considers that the process of instantiation — whether by humans or AI — might require a mix of various

elements, including thoughts, feelings, and environmental factors.

This holistic approach suggests that the ability to create complex entities depends on having all the necessary

components in the right proportions and in the right place.

This leads to another question: if emotions are a crucial ingredient, can robots truly instantiate new entities?

... Time will tell.

Courtroom defense

Thinking about instantiated objects in terms of courtroom defense offers a compelling perspective on how we validate the

existence of something like a mountain. In this analogy, an object—such as a mountain—is considered instantiated if

someone can provide convincing evidence of its existence in a courtroom setting. This approach emphasizes the role of

empirical evidence and persuasive argument in establishing reality.

In a courtroom, the existence of the mountain would be defended by presenting observations

and possibly testimonies from people who have seen the mountain. This evidence must be robust enough to

withstand scrutiny and convince a judge or jury of the mountain's existence.

If no one can present convincing evidence, or if the existing evidence is challenged and found unreliable, then the

existence of the mountain might be questioned or deemed unproven.

This courtroom analogy highlights that our shared reality is based not just on individual perceptions or

isolated observations,

but on a collective ability to demonstrate and verify those perceptions in a convincing manner.

Instantiation of artificial devices and social constructs

### Instantiation of Artificial Devices and Social Constructs

This concept is quite straightforward. For thousands of years, people have been using the principles behind the ISO

(Instantiation of Shared Objects) framework to create physical objects, establish social systems, and interact with metaphysical entities.

Nothing new or

surprising here. Essentially, it involves a collective agreement on the existence and nature of various things,

from buildings and bridges to governments and laws, allowing us to turn abstract ideas into concrete realities and

organize our societies effectively. This process is fundamental to how we build and maintain the world around us.

Instantiation of metaphysics: The privacy constraint

According to the GISO machinery, everything is made by people, and there must be no fundamental difference between

instantiating a material object or a metaphysical entity. The strategy is always the same – design a plausible story and

figure out reproducible practices delivering features characteristic of that entity. However, unlike natural systems

binding to all people, metaphysical entities are often binding only to groups of people. This binding introduces its own

peculiarities into the functioning of the GISO machinery. Let’s take an afterlife as an example. Consistent with the GISO

machinery, we assume our afterlife is the byproduct of our beliefs and practices. Members of different communities may

have different visions of the afterlife. For example, Bill may believe in heavens for himself and hell for John. John,

however, may have his own perception of his future, which may not be consistent with that of Bill. Having a metaphysical

entity binding to groups of people, introduces a prospect for contradictory claims by members of different groups. How

do we reconcile these contradictions?

To address potential contradictions between different individuals' beliefs about the afterlife, we introduce a

privacy constraint:

-

Each person is the sole authority over their own afterlife.

External opinions, such as Bill’s views on John's afterlife, are irrelevant. Only

John's personal beliefs and practices influence his afterlife.

Alternative Solutions:

- Override Mechanism: We could assume that people have the ability to override others'

projections about their future,

allowing individuals to reject external definitions of their metaphysical fate.

- Multiplicity of Identities: Another approach might be to allow for the proliferation of identities in the

afterlife. For example, there could be multiple versions of John: one as he perceives himself and another as Bill

perceives him. This scenario would acknowledge multiple coexisting narratives.

However, for the purposes of this discussion, I am choosing to adopt the privacy constraint as the simplest and most

straightforward solution. According to this principle, every individual has exclusive rights to their own afterlife.

What John believes about his future is the defining truth for his afterlife, regardless of others' opinions or beliefs.

This approach simplifies the complex issue of metaphysical contradictions by ensuring that each person's afterlife is

determined solely by their own convictions and actions.

An assumption that people are only responsible for their own beliefs entails certain ramifications and changes to the

established belief systems, particularly those which claim their exceptional rights on the fate of all people (and

almost all of them do). To reconcile these beliefs and integrate them into the multiverse framework, general statements,

spilling across the world boundaries, ideally, must be refined to make them consistent with the multiverse vision. The

scope of all other internal statements must be confined within the teaching itself. On the other hand, in real life, of

course, such amendments are hardly achievable, and a certain degree of inconsistency will always be present in the

established teachings.

According to the GISO (Instantiated Storied Object) framework, if people hold beliefs that lead to suffering — beliefs

one might perceive as morally wrong — the only option available is to try to persuade them to adopt what you

consider the right

beliefs and practices. However, changing someone's beliefs is often challenging, and success is not guaranteed. This

limitation suggests a certain tragic element inherent to the GISO framework's worldview, reminiscent of the themes

explored by Sophocles, the ancient Greek playwright who portrayed tragedy as a fundamental aspect of human existence.

In contrast, envision a different world, one inspired by Socrates, where the well-being of all people is a realistic and

achievable goal. In such a world, ensuring everyone's happiness would not depend on changing their beliefs but would be

a natural outcome of the system itself. Unfortunately, creating such a world, where universal well-being is assured,

remains a theoretical ideal. The practicalities of achieving this, if at all possible, are not yet understood. This

reflects a significant philosophical inquiry: whether it is feasible to construct a society where the happiness and

well-being of every individual are guaranteed, transcending the need to influence or correct personal beliefs.

### Afterlife

While pondering on the existence of an afterlife and asking why tangible evidence seems elusive and no one has

returned to tell us what the after-life looks like,

it's important to consider what we mean by "evidence" and "returning" from such a place.

Understanding "Coming Back"**

The concept of returning from the afterlife can be interpreted in several ways depending on cultural and spiritual

beliefs:

1. Reincarnation as understood in Buddhism involves a cycle of life, death, and rebirth, where what gets reborn is

not the individual consciousness or personality, but rather a causative element that links one life to the next. Here,

"coming back" doesn't carry personal memories but a causal continuity.

2. Spiritual Communication involves experiences reported in various religious practices, such as visions during

shamanic rituals, Christian mystical experiences, or deep meditation in Buddhism. These are believed to establish a form

of communication with spiritual realms or the afterlife.

3. Physical Resurrection is the most literal interpretation, suggesting a bodily return from death. This concept

faces significant challenges from the scientific perspective, as many natural processes are irreversible under the known

laws of physics. Our universe appears to operate under a rule set that does not include physical resurrection as a norm.

4. Multiverse travel considered in this manuscript assumes every newborn baby

is a visitor from a parallel universe. Amnesia, a side effect

of the travel to this specific universe, clouds the memories of these travelers.

Physical vs. Metaphysical Evidence

From a physical standpoint, the concept of resurrection contradicts our current understanding of natural laws,

suggesting why no empirical evidence of bodily resurrection exists in our universe. However, other universes might

theoretically operate under different rules where such phenomena are common.

In contrast, metaphysical or spiritual "return" from the afterlife is supported within specific communities through

documented spiritual experiences. These experiences are considered reproducible and valid within those communities'

belief systems. Individuals engaged in these practices report consistent and verifiable (to them) communications with

the afterlife, aligning with their spiritual teachings.

Personal and Community Beliefs about the Afterlife

The GISO framework suggests that the afterlife, much like past lives, is a construct influenced by personal and communal

beliefs and practices. What one believes and practices defines their afterlife.

GISO view allows for multiple interpretations of the afterlife to exist simultaneously, each as valid within its

own belief system as any other. It underscores the importance of personal belief systems in shaping one's metaphysical

experiences and suggests that while empirical evidence for some concepts may not be accessible in the traditional sense,

it can exist validly within specific cultural or spiritual contexts.

Summary

Let’s recap this chapter. According to the ISO machinery, to create a new real entity one has to design it

first, then implement that design in practice and finally test and maintain it. This strategy applies perfectly well to

conventional artificial entities be it a physical aggregate or a social construct. Unfortunately, it does not apply to

natural systems which seem to exist by themselves often independent of our theories and practices.

To generalise the ISO machinery towards natural systems, we assumed our collective knowledge of such systems to be

equivalent to these systems. If no one in the whole universe knows what is inside a closed box, then its content

exists in a state of a superposition of hypothetical objects which can fit inside. When we open that box for the first

time and look inside, the process of the observation collapses that superpositional state into a single particular

outcome – an object we can observe. The process of the observation instantiates that particular object out of the range

of abstract possibilities. And vice versa, when the knowledge of the particular object is wiped out completely from the

memory of all human kind (including all circumstantial evidence which may point to that object), we assume that object

to transform back into the abstract hypothetical state. This Generalised ISO (GISO) machinery encourages a three-layered

structure of the world ontology comprising the realms of abstract and particular entities and also the realm of

human beings considered neither abstract nor particular.

This Generalised ISO machinery applies across natural, social and metaphysical domains. To avoid contradictions when

instantiating natural systems, we introduced the ordering constrain (the first instance rules). Analogously, in

metaphysical domain we introduced the privacy constraint (one is the master of his/her own future)

Why do we care about extending the ISO machinery towards natural systems?

Because otherwise we would always have doubts about the existential status of social constructs and metaphysical

entities - how do we know they are real if they are so different from the natural systems? The GISO

machinery, by offering the same language applicable across different domains, makes it easier for us to believe they are

all of the same kind - social constructs. According to the GISO machinery our customs, morals, feelings, regulations,

gods are as much real as are the mountains and the oceans.

With this comprehensive framework in place, the next chapter will explore how to design and instantiate a storied

multiverse.

The alien

He paused for a moment and then gasped: he can design and instantiate his own world. Instead of trying to figure out

which one out of many established worlds is real, he can create a new one from scratch. All is needed is to

design key features and practices, and then gather a team of friends to instantiate and maintain it.

So obvious and so simple. How did he miss it for so long?